Spore-forming bacteria that are common in the human gut can affect our nutrition and health. Most of these bacteria are beneficial, but some species in the group, like anthrax-causing Bacillus and Clostridium difficile, are pathogens that cause diarrhea, respiratory complications, inflammation, and—in some cases—death.

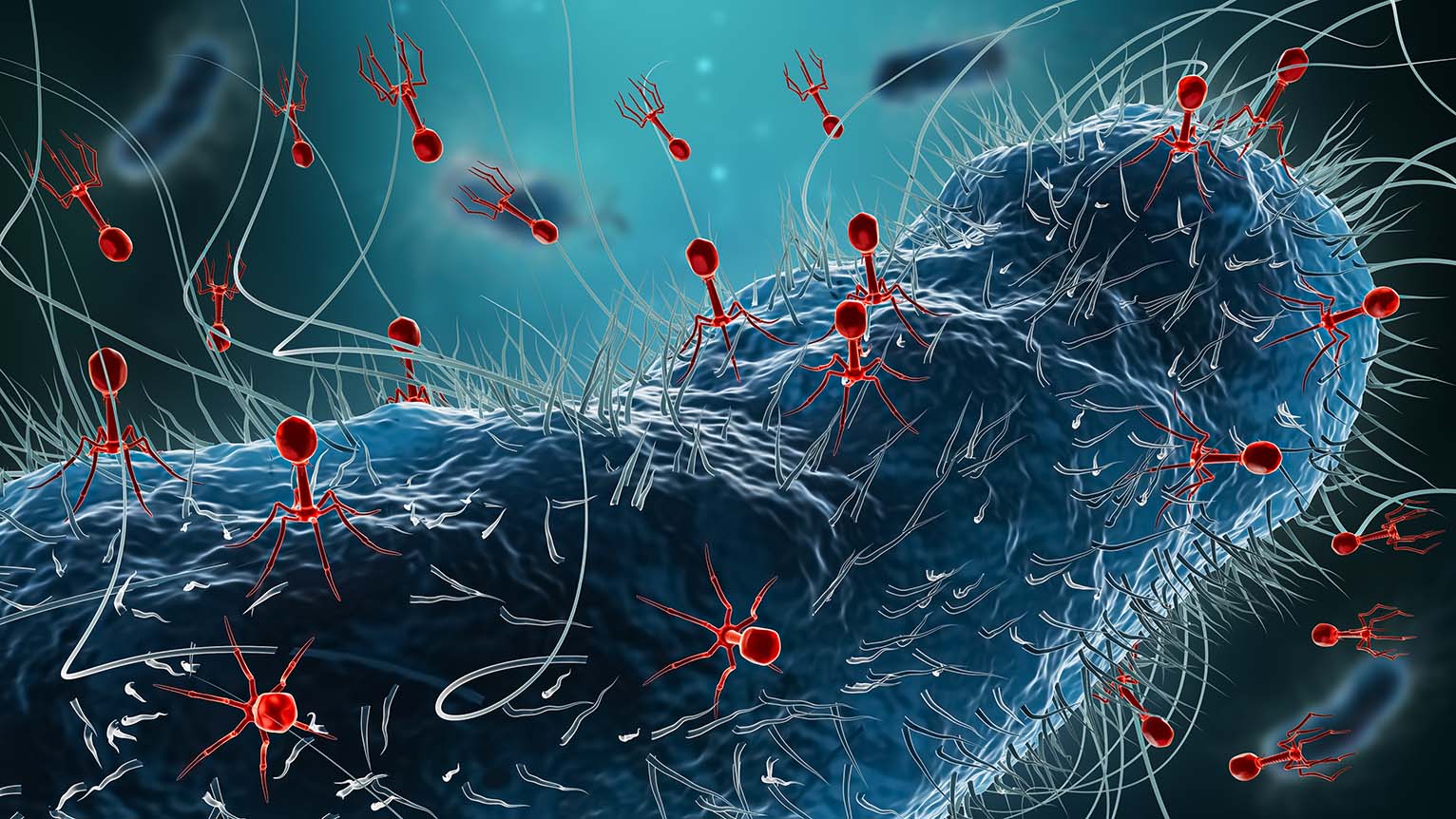

Daniel Schwartz is a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Jay Lennon, a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences Department of Biology at Indiana University Bloomington. Recent studies involving phages (viruses that infect and often kill bacteria) by Schwartz and Lennon in collaboration with scientists in the lab of Kelly Wrighton at Colorado State University found that spore-forming bacteria may escape infection by entering a dormant state that protects them from virus infection. The team’s recent article published in the journal mBio describes how phages in the human gut acquire sporulation genes from bacteria that they may use to hijack their hosts.

"The bacteria we study produce dormant spores thought to play an important role in the bacteria’s colonization, persistence, and transmission," explains Schwartz. "Phages acquire bacterial genes and use them to alter host metabolism in ways that enhance phage reproduction and survival. Most auxiliary genes replace or modulate enzymes that are used by the host for nutrition or energy production; however, phage biology is affected by all aspects of the host’s physiology, including decisions that reduce metabolic activity of the bacterial cell."

The College of Arts

The College of Arts