As the COVID-19 pandemic continues its global spread, vaccine development is on everyone’s mind. Indiana University’s John Patton is no exception.

Patton, professor of biology and Blatt Chair of virology in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington, has been studying viruses for more than 30 years. His main focus has been on rotavirus. As many parents know, rotavirus can infect infants and young children, causing nausea and diarrhea. Today, most infants in the United States receive a rotavirus vaccine, meaning over the last 20 years or so, “rotavirus as the main cause of sending young kids to the hospital has disappeared,” Patton says.

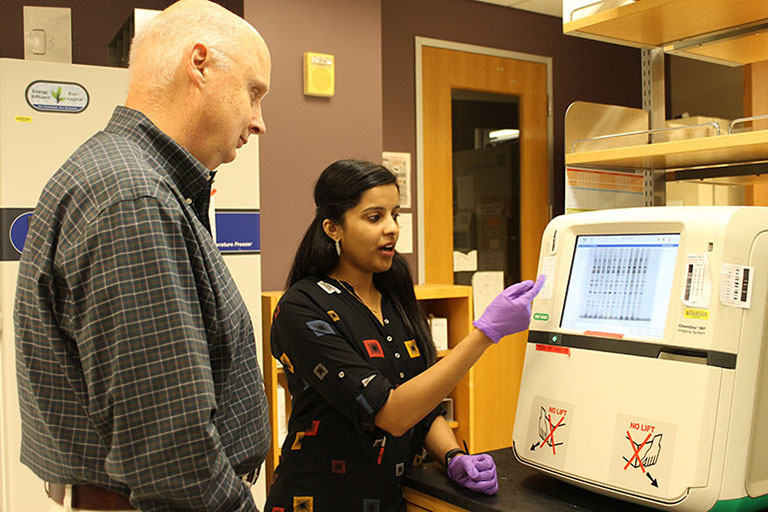

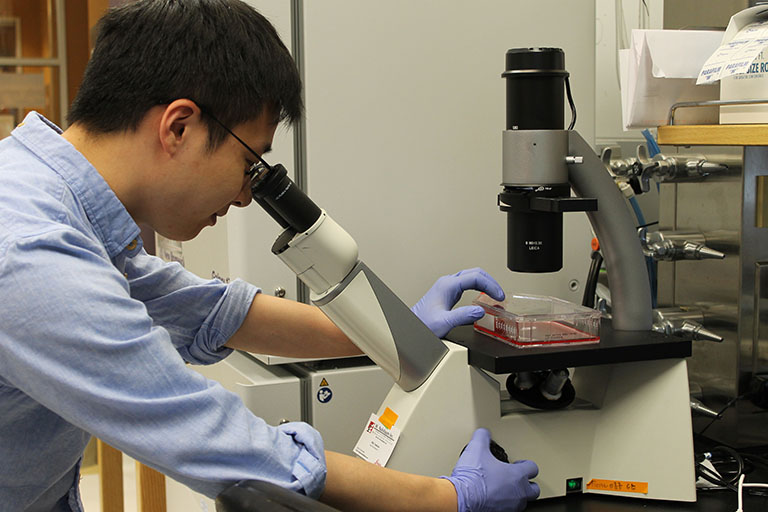

That’s not the case in developing countries, however, where rotavirus vaccines have been less effective, for reasons that remain unclear. Patton and his laboratory colleagues have continued their research into the biology of rotavirus and its development as a vector for creating effective vaccines against other viruses.

Then came COVID-19. As the virus began racing from country to country, Patton realized in early February that his lab was primed to work on a COVID-19 vaccine.

“As a virologist,” Patton says, “I’m always thinking about other viruses, whether it’s flu or MERS or SARS. I’m always processing how I might go about investigating newly emerging viruses and uncovering methods for controlling their diseases.”

The potential solution Patton’s lab is working on now is unique. Instead of taking a “flu-like approach” to creating a new vaccine, Patton and his team are leveraging the lab’s ongoing work exploring rotavirus to develop a vaccine that will protect children against COVID-19.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts