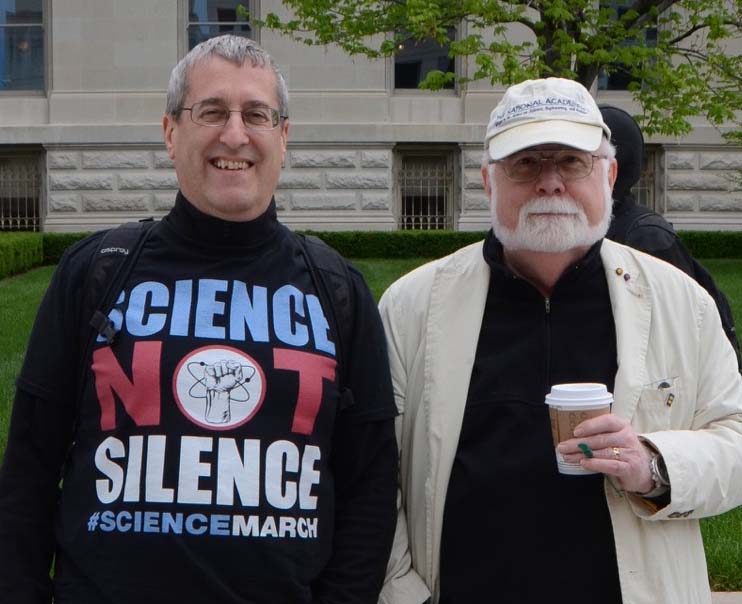

Participation in the march was in no small part driven by a recent White House budget proposal to significantly reduce government-funded research. Funds would instead be focused “in the highest priority research and training activities.” But, the history of science and innovation tells us instead that we cannot predict what research has the best chance of yielding the strongest benefits for humanity. An example from Indiana University’s illustrious history of research in microbiology makes this clear.

In the 1960s, IU Professor Thomas Brock became interested in the distribution of photosynthetic microorganisms along the thermal gradients created by the outflow channels of hot springs. In 1966, he obtained an ~$88,000 grant from the National Science Foundation for a project titled, “Biochemical Ecology of Yellowstone Hot Springs.” It’s fair to say that few people would pick this research as high priority for funding if likelihood of benefitting society was a criterion. As Brock conducted his studies, he became curious about the bacteria living in the hot springs. Around 1968, his undergraduate student, Hudson Freeze [BA '68], isolated a bacterial species, which they named Thermus aquaticus, from the hot springs and began to study the basis for its ability to survive at high temperature. Freeze found that the bacterium’s enzymes were extremely resistant to high temperatures, even to boiling.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts