A team of scientists led by Florian Krammer at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai just completed the first human clinical trial of what they hope will be a universal flu vaccine.

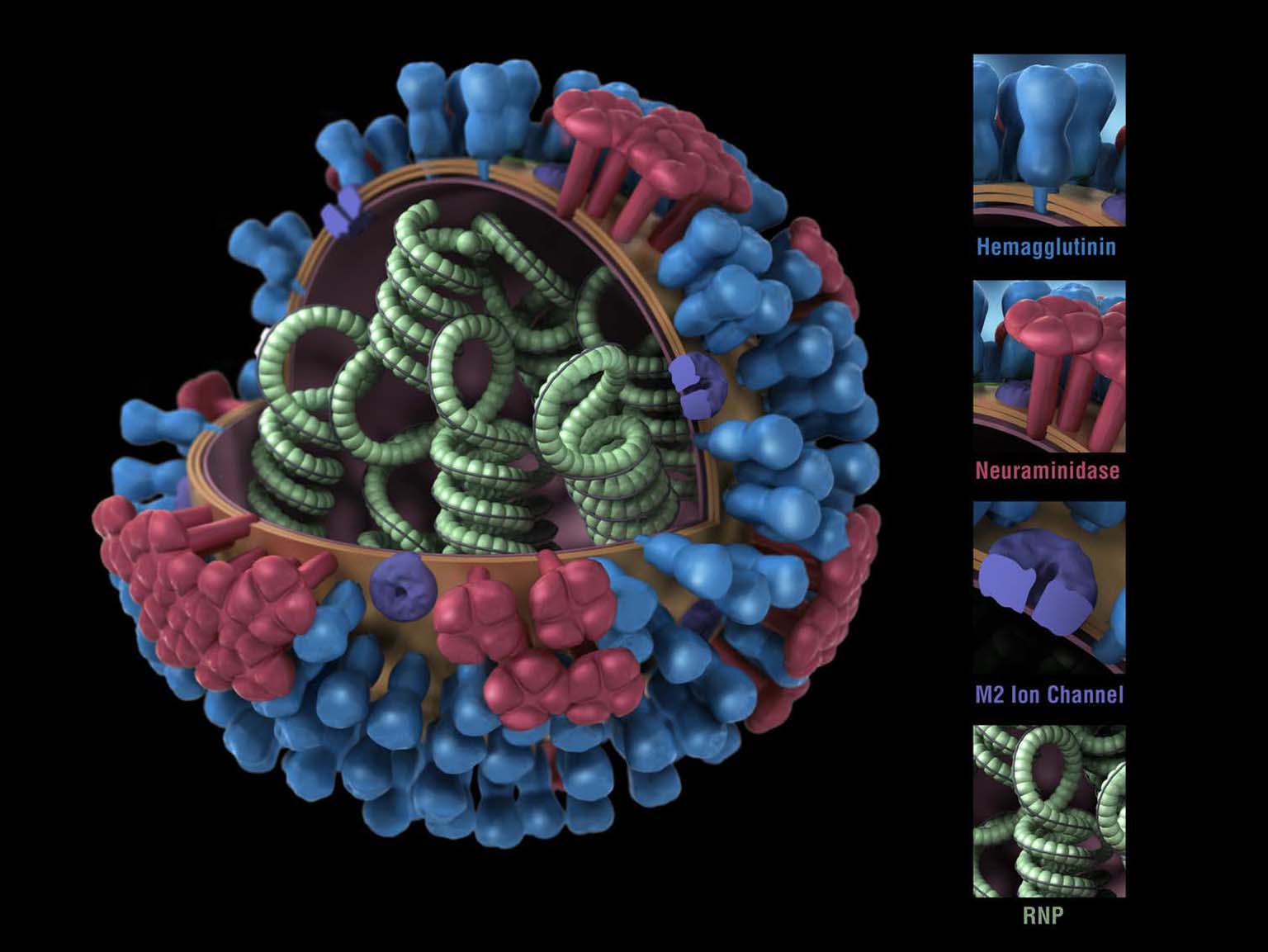

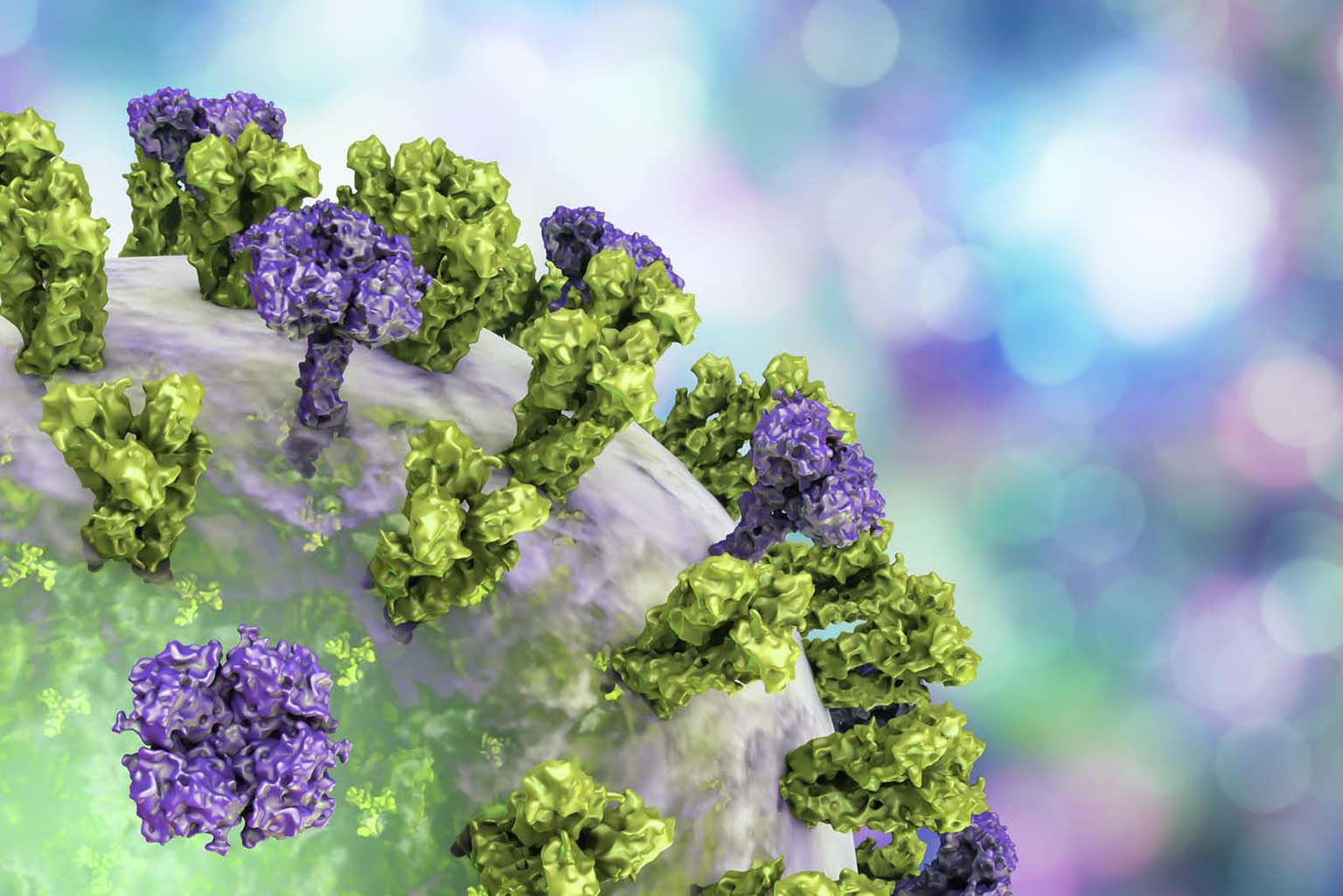

The researchers used recombinant genetic technology to create flu viruses with “chimeric” HA proteins—essentially a patchwork quilt built from pieces of different flu strains.

Volunteers for the clinical trial received two vaccinations separated by three months. The first dose consisted of an inactivated H1N1 virus with its original HA stalk but the head portion from a bird influenza virus. Vaccination with this virus induced a mild antibody response to the foreign head, and a robust response to the stalk. This pattern meant that the immune systems of the subjects had never encountered the head before, but had seen the stalk from previous flu vaccinations or infections.

The second vaccination consisted of the same H1N1 virus but with an HA head from a different bird virus. This dose elicited, again, a mild antibody response to the new head, but a further boost in response to the HA stalk. After each vaccine dose the subjects’ stalk antibody concentrations averaged about eight times higher than their initial levels.

Researchers found that even though the vaccine was based on the HA stalk of the H1N1 virus strain, the antibodies it elicited reacted to HA stalks from other strains too. In lab tests, the antibodies from vaccinated volunteers attacked the H2N2 virus that caused the 1957 Asian flu pandemic and the H9N2 virus that the CDC considers to be of concern for future outbreaks. The antibodies did not react to the stalk of the more distantly related H3 viral strain.

The antibody response also lasted a long time; after a year and a half, the volunteers still had about four times the concentration of antibodies to the HA stalk in their blood as when the trial started.

Since this was a phase 1 clinical trial testing only for adverse effects (which were minimal), the researchers didn’t expose vaccinated people to the flu to test if their new antibodies protected them.

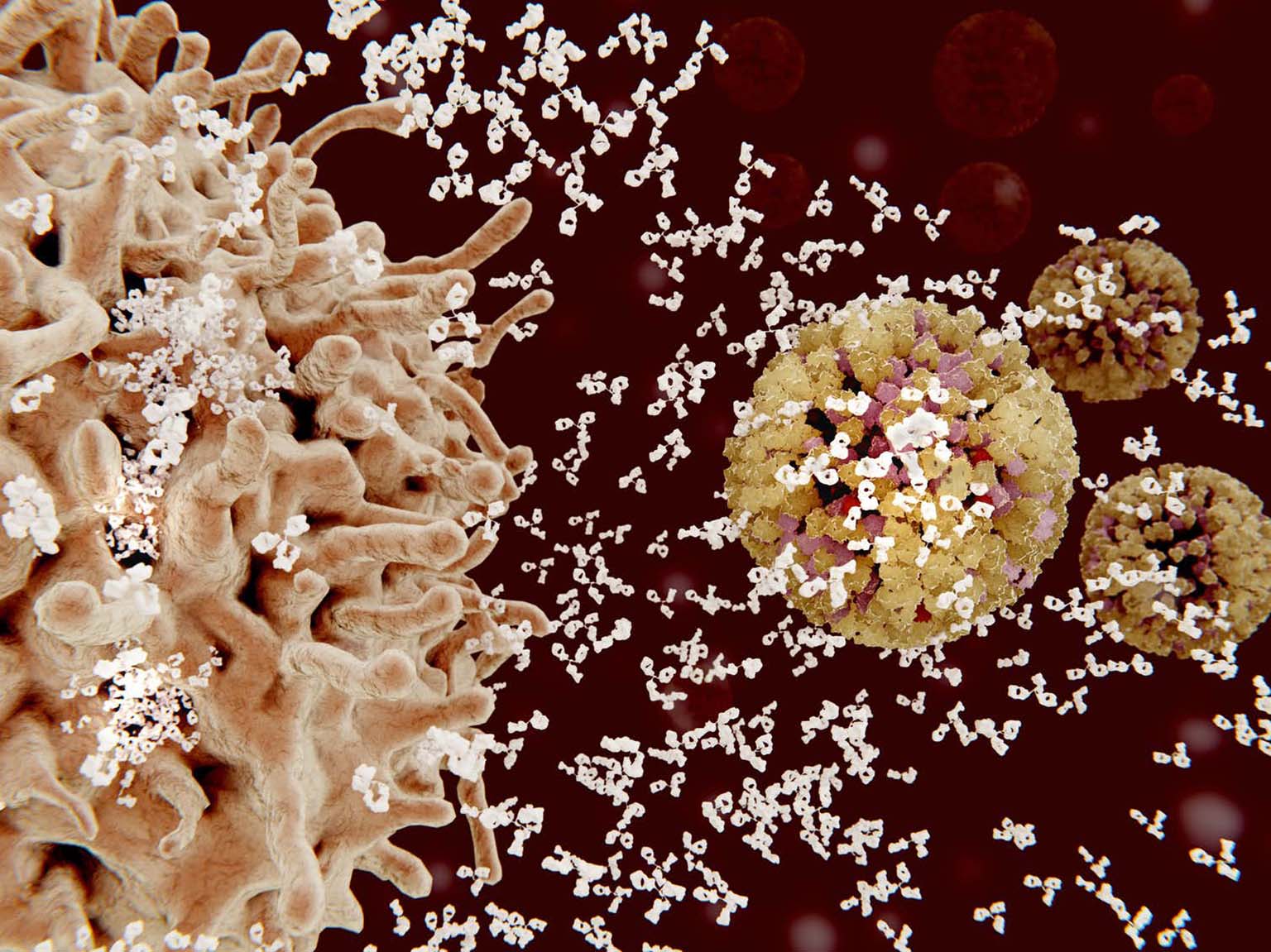

However, they did inject the subjects’ blood serum, which contains the antibodies, into mice to see if it would protect them against the flu virus. Getting a shot of serum taken from volunteers a month after receiving the booster shot, when antibody levels were high, led to mice being 95% healthier after virus exposure than mice who got blood serum from nonvaccinated volunteers. Even the mice who received serum that was collected from vaccinated volunteers a year after the start of the trial were about 30% less sick.

These results show that vaccination with a chimeric flu protein can provide long-lasting immunity to several different strains of the influenza virus. Scientists will need to continue optimizing this approach so it works for different types and strains of influenza. But the success of this first human trial means you may one day get a single shot and, at last, be free from the flu.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts