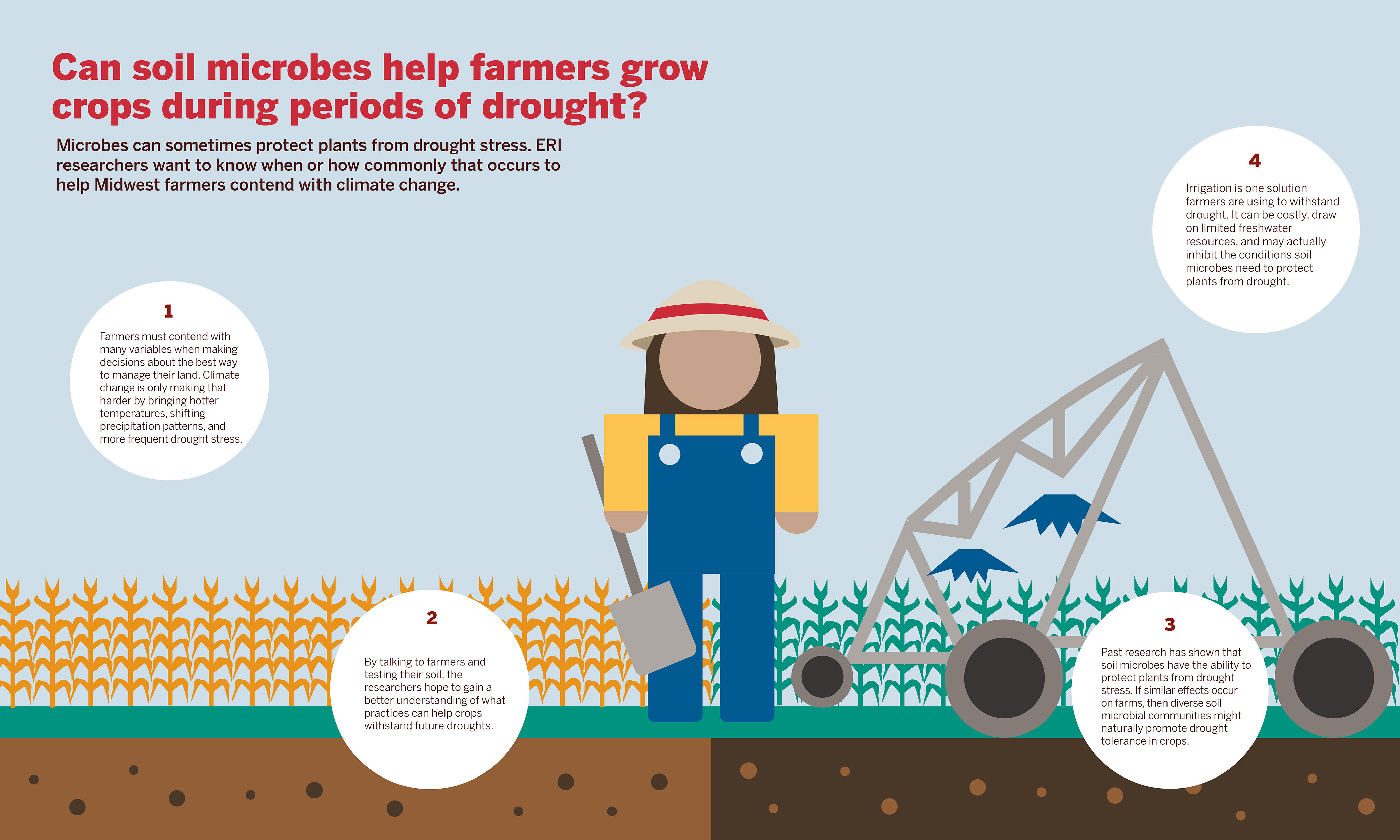

Hotter temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and drought-stressed crops are three factors farmers in the Midwest are becoming increasingly familiar with as climate change progresses. To combat these trends, farmers are turning to irrigation, which can be costly to install, draw upon limited freshwater resources, and may actually inhibit natural drought-protection assets hiding right under farmers’ feet.

An Indiana University team led by researchers affiliated with IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute (ERI) has been awarded $1.4 million from the National Science Foundation to study how farmers and the soil microbes on their farms respond to drought. The findings could help farmers identify efficient practices to adapt to a hotter climate.

By talking to farmers in Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan and testing soil samples from their fields—both through greenhouse experiments and by studying soil microbes’ genetics—the researchers hope to gain a better understanding of what agricultural practices promote vibrant microbial communities and what farmers can do to withstand future droughts.

“We know that microbes can sometimes protect plants from drought stress, but we don’t know when or even how commonly that occurs,” said Jen Lau, an associate professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Biology. “By describing the microbial communities from all these different farms and measuring how much these microbes protect plants from drought stress, we can hopefully start to predict when these microbial communities are beneficial and what farmers can do to cultivate them.”

Lau, an ecologist, is leading the 5-year study along with IU sociologist and ERI Fellow Matt Houser, IU historian and ERI Fellow Elizabeth Grennan Browning, IU ecologist Jay Lennon and Michigan State colleagues Sarah Evans and Sandy Marquart-Pyatt.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts