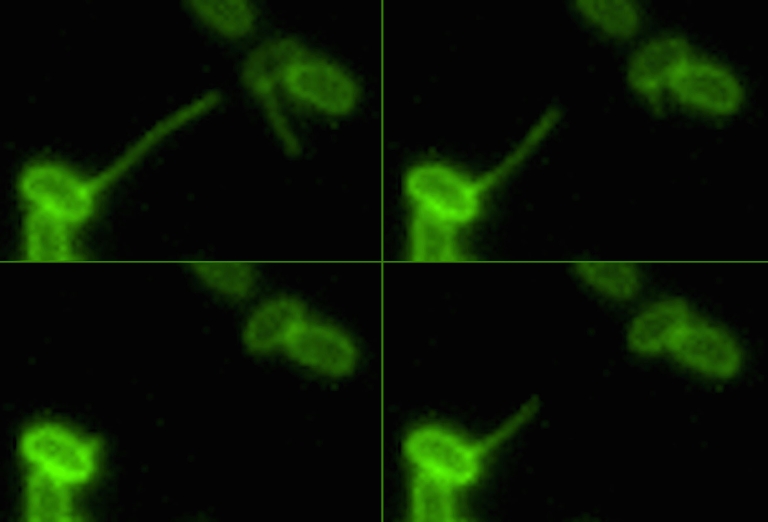

A new imaging method invented at IU leads to a discovery about how bacteria use thin hair-like surface appendages called pili for 'natural transformation.'

A new study from Indiana University has revealed a previously unknown role a protein plays in helping bacteria reel in DNA in their environment -- like a fisherman pulling up a catch from the ocean.

The discovery was made possible by a new imaging method invented at IU that let scientists see for the first time how bacteria use their long and mobile appendages -- called pili -- to bind to, or "harpoon," DNA in the environment. The new study, reported Oct. 18 in the journal PLOS Genetics, focuses on how they reel their catch back in.

By revealing the mechanisms involved in this process, the study's authors said the results may help hasten work on new ways to stop bacterial infection.

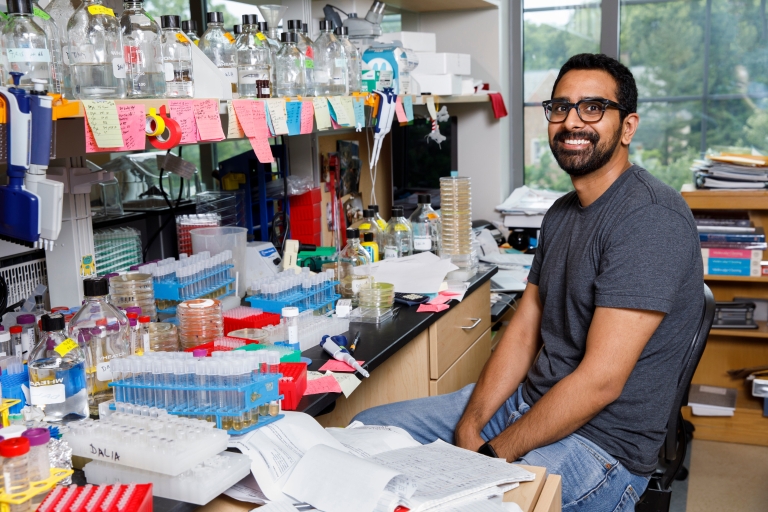

"The issue of antibiotic resistance is very relevant to this work since the ability of pili to bind to, and 'reel in,' DNA is one of the major ways that bacteria evolve to thwart existing drugs," said Ankur Dalia, an assistant professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Biology, who is senior author on the study. "An improved understanding of this 'reeling' activity can help inform strategies to stop it."

The act of gobbling up and incorporating genetic material from the environment -- known as natural transformation -- is an evolutionary process by which bacteria incorporate specific traits from other microorganisms, including genes that convey antibiotic resistance.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts