The work is reported today in the journal Nature Microbiology.

"Horizontal gene transfer is an important way that antibiotic resistance moves between bacterial species, but the process has never been observed before, since the structures involved are so incredibly small," said senior author Ankur Dalia, an assistant professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Biology.

"It's important to understand this process, since the more we understand about how bacteria share DNA, the better our chances are of thwarting it," he added.

Nearly 1 million people are affected by antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year, according to the World Health Organization. WHO has found evidence of these strains in nearly 490,000 people with tuberculous and 500,000 people with other infectious diseases.

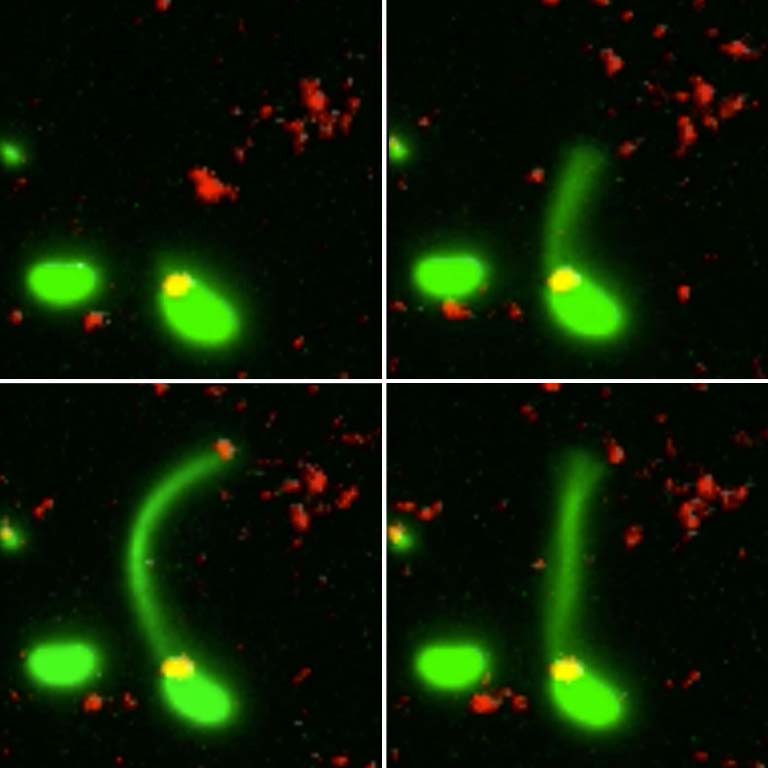

The bacterium used in the study was Vibrio cholerae, the microbe that causes cholera. The bacterial structures used to catch DNA in the environment are extremely thin, hair-like appendages called pili.

Although scientists were aware that pili play a role in DNA uptake, Dalia said that direct evidence demonstrating how they work was lacking until this study. In order to observe pili in action, the scientists used a new method invented at IU to "paint" both the pili and DNA fragments with special glowing dyes.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts