Improved method to observe cell structures involved in biofilm reveals how bacteria cling to surfaces, leading to major infrastructure, health problems

A study led by scientists at Indiana University reports a new method to determine how bacteria sense contact with surfaces, an action that triggers the formation of biofilms—multicellular structures that cause major health issues in people and threaten critical infrastructure, such as water and sewer systems.

It's estimated that biofilms contribute to about 65 percent of human infections and cause billions in medical costs each year. They infamously played a role in unsafe coliform levels in the water supply of 21 million Americans in the early 1990s and, more recently, likely played a role in several outbreaks of Legionnaire's disease in Flint, Michigan. They also regularly contribute to global cholera outbreaks.

Biofilms cause serious damage in industry, including clogging water filtration systems or slowing down cargo ships by "biofouling" the vehicles' hulls, costing an estimated $200 billion per year in the U.S. alone. There are also beneficial biofilms, such as those that aid digestion or help break down organic matter in the environment.

The researchers, led by IU Distinguished Professor of Biology Yves Brun, discovered the way bacteria detect and cling to surfaces. The researchers also discovered a method to trick bacteria into thinking they are sensing a surface.

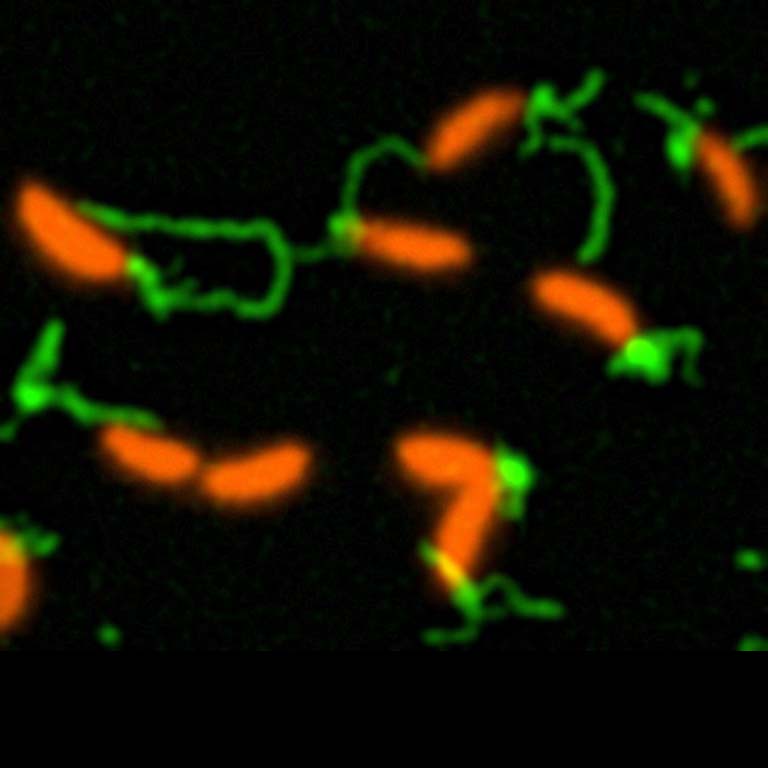

The team showed that bacteria use ultra-thin hair-like appendages called pili that extend from the cell and retract dynamically to feel and stick to surfaces and ultimately produce biofilms. The pili stop moving after sensing a surface, after which the bacteria start producing an extremely sticky substance, or "bioadhesive," that drives attachment to surfaces and biofilm formation.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts